10.1 ROLE OF THE CHART OF ACCOUNTS

The chart of accounts is the set of general ledger accounts defined for a particular accounting company. In earlier general ledger systems, the chart of accounts primarily supported financial statement preparation and represented an item of interest solely to accounting management. Aided by the capabilities of automated general ledger systems, this role has evolved to assist with a broader range of management and operational business processes, including

• Reporting and controlling departmental activity.

• Generalized management reporting.

• Reporting tax-basis accounting information.

• Reporting cash flow information.

• Preparing the annual profit plan.

In addition to this, the traditional role of a chart of accounts still applies: it is still the basis for accounting and summary financial reporting.

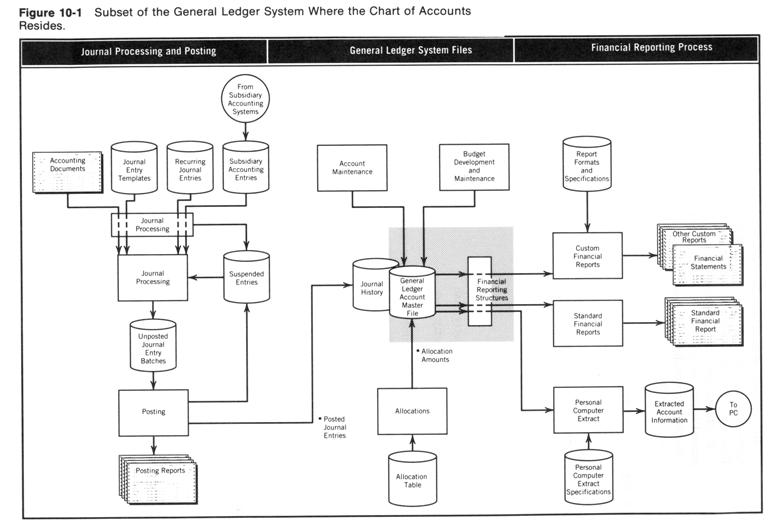

Figure 10-1 shows the portion of the general ledger system in which the chart of accounts resides: the general ledger master file and the financial reporting structures. Even though information held in these two system structures is a small part of the overall system, its effect is felt throughout. For example, journal processing feeds the lowest level of accounts and the financial reporting process must pull information from these accounts.

Indeed, a broader definition of the term chart of accounts must convey that the chart of accounts forms the basis for storing, accessing, and reporting all financial information for that accounting company. One should not think of the chart of accounts only in terms of a list of accounts. In a very real sense, the chart of accounts represents a model of the organization. In a modern environment, the chart of accounts is usually a multidimensional structure represented in the account numbers, defined through the account number's coding and summarized through financial reporting structures.

Accounting and financial management must understand the relationship between the chart of accounts and various general ledger budgeting and reporting processes to make good use of available general ledger system features. Different systems have specific strengths and weaknesses in their implementation of the chart of accounts. This can present both problems and opportunities for any particular organization using an automated general ledger. Sometimes a particular system can appear to have problems or not fit an organization's needs when actually the manner of its use is the cause these problems. Even full-featured general ledger systems, which tend to be very complex, can be easily misused. For example, general ledger systems generally provide enough latitude for someone to easily make improper decisions about how the system should be set up. Imagine rewriting the financial report writer's report specifications for all the financial reports whenever a corporate reorganization occurs. This is what can happen when a financial report writer does not correctly use chart of account features for financial reporting.

In many cases misuse of system features can be avoided through correct use and understanding of how the chart of accounts is implemented in a particular automated accounting system. Prudently applying the system's capabilities helps make the system work for the organization, rather than vice versa. The concepts in this chapter provide an outline of a framework for understanding how different general ledger systems work as well as the strengths and weaknesses of their individual approaches to structuring a chart of accounts and creating financial reports from this structure.

10.2 BASIC ACCOUNT ORGANIZATION

An organization's financial reporting needs may require that the accounting system capture and retain many different pieces of related financial information. For example, a business may require the financial reporting system to report on the following pieces of cash-related information:

• Current assets.

• Total cash.

• Operating cash.

• Newtown Plant petty cash.

• Brooklyn Plant petty cash.

Similarly, the same business may have requirements for reporting different types of labor and other expense information:

• Total expenses.

• Operating expenses.

• Direct labor expenses.

• Indirect labor expenses.

• Newtown Plant fabrication department labor expenses.

• Newtown Plant composites department labor expense.

To retain accounting and financial information on such different, but related items, many businesses organize their chart of accounts such that each account number contains two components or dimensions:

1. The natural account identifies what the financial activity is.

2. The budget center identifies who is responsible for the activity.

Referring to the previous example, this means assigning values to natural accounts including:

1000 Current Assets

1100 Total Cash

1110 Petty Cash

1120 Operating Cash

5000 Total Expenses

5100 Operating Expenses

5110 Direct Labor Expenses

5120 Indirect Labor Expenses

These are pure accounting classifications, absent of any reference to geographic location, organizational unit, or product type. Similarly, the pieces of financial information noted earlier identify organizational areas of financial responsibility, referred to as budget centers, that can also be assigned numerous values:

000 Corporate

100 Newtown Plan

110 Newtown Plant Fabrication Department

120 Newtown Plant Composites Department

200 Brooklyn Plant

Taking this process one step further, this convention for account organization creates account numbers by combining a natural account with a budget center to form an account number

1000-000 Current Assets

1100-000 Total Cash

1110-100 Newtown Plant Petty Cash

1110-200 Brooklyn Plant Petty Cash

1120-000 Operating Cash

The complete list of account numbers becomes the chart of accounts. Only with each account number does the system store actual financial information. The earlier lists of valid values for either component define the domain of either component, establishing a standard or convention that should be followed when adding new account numbers to the chart of accounts. The dashes neatly separate the components of each account number and allow an accountant to easily recognize the account number and its components, just as someone might use similar delimiters to identify the significant pieces of information in a telephone number, large dollar amount, or date.

Note that this example shows a description for each account that includes budget center descriptive information (e.g., Newtown Plant Petty Cash). Many general ledger systems store account descriptions for each detailed account allowing this to occur. A short cut to this approach uses account descriptions that describe only the natural account (e.g., Petty Cash). Either approach is acceptable. The first requires a much greater number of descriptions to maintain, but provides the flexibility of naming each specific account. The second uses fewer descriptions and requires less maintenance, but it requires accountants and others to recognize the budget centers for particular accounts solely based on the budget center number. One particular design offers the best of both approaches: storing both the natural account and budget center descriptions separately, but concatenating them together to form an account description used for reports and screens.

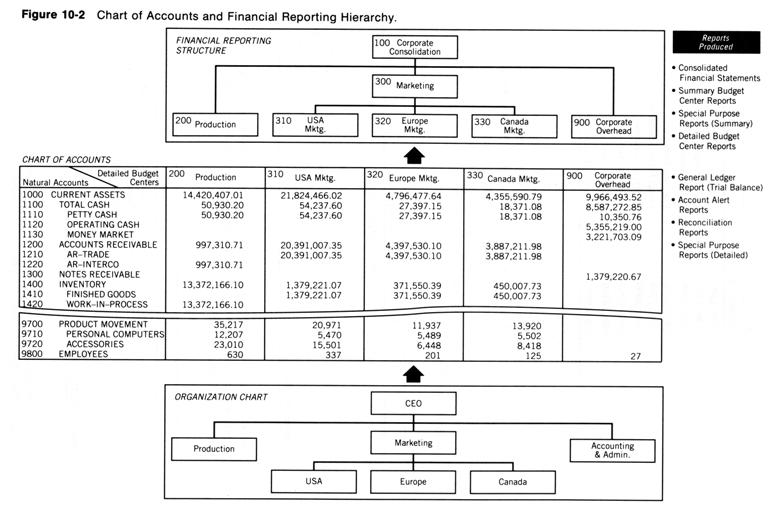

The previous example helps explain the basics of chart of account organization, but it does not present a complete picture of the concepts used to organize accounts in modern, automated accounting systems. Figure 10-2 shows the overall organization of a two-dimensional chart of accounts in greater detail. Each cell in the matrix constitutes an account. This more detailed example brings together many concepts discussed throughout this chapter and, in doing so, raises a series of questions about chart of account organization.

• Natural Accounts: What approaches are used to further classify the natural account numbers and represent sub classifications of natural account information, such as Current Assets, Cash, and Petty Cash?

• Account Summarization: How are summary total amounts for natural account information, such as Current Assets, Total Expenses, and Operating Expenses, maintained?

• Responsibility Accounting and Reporting: How are relationships among different organizational units, such as the Newtown Plant, the Brooklyn Plant, and the Corporation Organization, represented in the chart of accounts?

• Multidimensional Account Numbering Systems: How can a particular class of information, such as expenses, be neatly combined across many different natural accounts and plants.

Answers to these questions, as well as a better understanding of Figure 10-2, come by looking in detail at conventions, approaches, and general ledger system features for organizing the chart of accounts.

NEXT MONTH'S TOPIC: Natural Accounts